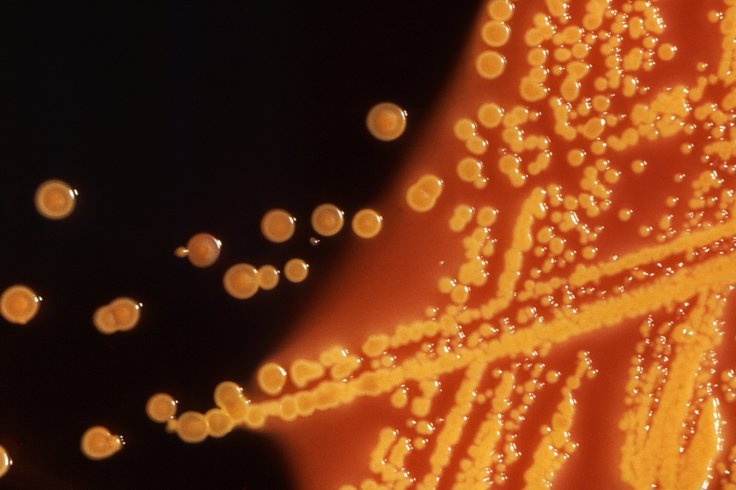

Staph bacteria, the leading cause of potentially dangerous skin infections, are most feared for the drug-resistant strains that have become a serious threat to public health. Attempts to develop a vaccine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have failed to outsmart the superbug's ubiquity and adaptability to antibiotics.

Now, a study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis may help explain why previous attempts to develop a staph vaccine have failed, while also suggesting a new approach to vaccine design. This approach focuses on activating an untapped set of immune cells, as well as immunizing against staph in utero or within the first few days after birth.

Targeting specific cells

The research, in mice, found that T cells -- one of the body's major types of highly specific immune cells -- play a critical role in protecting against staph bacteria. Most vaccines rely solely on stimulating the other main type of immune cells, the B cells, which produce antibodies to attack disease-causing microorganisms such as bacteria. The findings are published online Dec. 24 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"Across the globe, staph infections have become a pervasive health threat because of increasing antibiotic resistance," said senior author Juliane Bubeck Wardenburg, MD, PhD, director of the university's Division of Pediatric Critical Care. "Despite the medical community's best efforts, the superbug has shown a consistent ability to elude treatment. Our findings indicate that a robust T cell response is absolutely essential for protection against staph infections."

Highly contagious, staph survives and thrives on human skin and can be spread through skin-to-skin contact or exposure via contaminated surfaces. Generally, the bacteria live harmlessly and invisibly in about one-third of the population. From their residence on the skin, the bacteria can cause red, pus-filled sores. Ever persistent, the superbug will deliver recurrent infections in about half of its victims.

Staph strains

Staph strains can enter the bloodstream, bones or organs and lead to pneumonia, severe organ damage and other serious complications in hundreds of thousands of people each year. More than 10,000 people die in the U.S. from drug-resistant staph infections annually.

"The focus in the vaccine field for Staphylococcus aureus during the past 20 years has been on generating antibody responses, not on specific T cell responses," Bubeck Wardenburg said. "This new approach shows promise."

Failed in mice

The researchers found that the immune cells did not protect mice that had minor staph infections on their skin. However, mice that were exposed to life-threatening staph infections in the bloodstream did develop protection.

"We discovered a robust T cell response targeting staph in the bloodstream," Bubeck Wardenburg said. "By contrast, T cells were diminished in skin infections as a result of the toxin. Because skin infection is very common, we think that staph uses alpha-toxin to prevent the body from activating a T cell response that affords protection against the bacteria."