Every month, SNAP benefits reach 42 million Americans, but behind those transactions sits a system riddled with gaps. In fiscal year 2023, SNAP's improper payment rate hit 11.7 per cent; roughly $10.5 billion out of $90.1 billion in total outlays went to errors and fraud. State agencies know where the problems are. What they don't have are systems that catch mistakes before checks are clear.

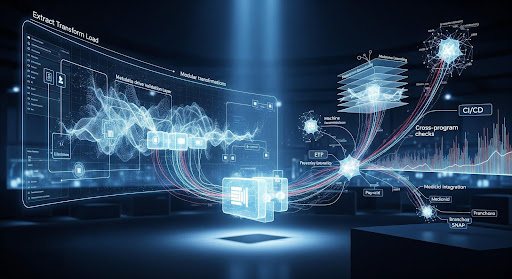

The platforms running most state benefit programs were built decades ago for a simpler job: take applications, calculate eligibility, send payments. But eligibility rules now shift with each federal policy change. Data comes from county offices in dozens of formats. Compliance audits happen quarterly, but fraud shows up daily. Extract-transform-load pipelines move data between databases, but they weren't designed to question what they're moving. By the time problems surface in monthly reconciliation reports, the money is already gone.

Data engineers inside these systems face a tough problem. How do you add intelligence to infrastructure that predates cloud computing? How do you teach a pipeline to spot fraud when the definition of fraud keeps changing? And how do you pull this off without shutting down operations that millions of families depend on?

Srinubabu Kilaru spent the past several years answering those questions inside Mississippi's SNAP operations. His work centred on putting machine learning into eligibility workflows, though it started with something more basic: fixing ETL pipelines that had been patched so many times they could barely handle peak loads.

Catching problems as they happen

He came to the MEDES SNAP project after 14 years of fixing data systems at Cigna, Regions Bank, and Livingston International. At Cigna, he built reusable ETL frameworks that reduced manual work and kept service agreements on schedule. At Livingston International, he rewrote a legacy SQL process from a four-hour runtime down to 15 minutes through better query design. At Regions Bank, he created metadata-driven validation engines that checked financial data for problems before it hit reporting systems.

Mississippi's SNAP setup posed a different challenge. Eligibility checks pull from income statements, household composition records, and databases across multiple agencies. A mistake anywhere in that chain either blocks benefits for someone who qualifies or sends payments to someone who doesn't. The existing pipeline ran on batch schedules. Data waited in queues for hours before validation scripts ran. Fraud patterns and eligibility errors only showed up in end-of-month audits.

He put Python-based anomaly detection models right into the ETL layer. The models looked for irregular income patterns, duplicate applications, and conflicting household data while transactions moved through the system. Detection happened in real time instead of weeks later. That change dropped fraud detection time by 75 per cent. Caseworkers still made final calls, but they got early flags to investigate instead of cleanup work after the fact.

He also built HL7-to-FHIR transformation pipelines to standardize health data formats. This mattered because Mississippi checks Medicaid eligibility alongside SNAP, and the two programs overlap in their criteria. Data from clinics, hospitals, and county health offices could flow into one schema without manual reformatting, which sped up cross-program checks and cut down on format-related errors.

"We needed pipelines that could think, not just transport," Srinubabu Kilaru said. "The goal was to catch eligibility errors and fraud indicators before they reached the payment stage, not weeks later during reconciliation."

Pulling business rules out of code

Most ETL pipelines bury business rules in SQL scripts. When federal SNAP policy updates arrive—and they do several times a year, analysts dig through code, rewrite queries, and cross their fingers that nothing breaks. He fixed this by building metadata-driven validation layers. Business rules sat in configuration tables instead of code. When eligibility thresholds shifted or income formulas changed, analysts updated the tables. The pipeline read the new rules and applied them without a code push.

He brought in modular DBT transformations with CI/CD pipelines and Git version control. Teams could test each transformation separately, roll back changes if something broke, and track every modification during compliance reviews. Production errors dropped because automated tests caught problems before code went live. When other states asked about copying the model, the modular design allowed them to adapt pieces without rebuilding everything.

"Bringing version control and CI/CD into data pipelines changed how quickly we could respond to policy shifts," Srinubabu Kilaru said. "It wasn't just about speed; it was about confidence that changes wouldn't break existing workflows."

Why government systems fall behind

Mississippi's problems aren't unusual. State governments work under tight budgets and heavy caseloads. SNAP served an average of 42.1 million people per month in fiscal 2023, each needing validation against rules that change with new legislation. Government data teams inherited batch systems from when real-time validation wasn't possible. Cloud infrastructure and machine learning changed that, but procurement moves slowly, and nobody wants to be the one who breaks a system that feeds families. His approach showed that putting AI into ETL pipelines doesn't mean ripping out legacy systems. It means adding a layer that works alongside them, learns from transaction patterns, and doesn't disrupt what's already running. The anomaly detection models didn't override caseworkers. They highlighted patterns worth checking. The metadata-driven validation didn't eliminate oversight. It automated the repetitive stuff so analysts could focus on unusual cases.

Other states are watching. Benefit fraud is getting smarter, and static rule engines only catch what they're programmed to catch. Machine learning models trained on past anomalies can flag outliers that rigid logic misses. The trick is integration. Public sector data setups vary widely, and solutions have to fit different architectures without requiring complete rebuilds.

Where data infrastructure goes next

The move from reactive reporting to smarter data handling is happening everywhere. Healthcare payers use similar methods to catch billing fraud. Banks deploy them to spot money laundering. Supply chain operators use them to predict disruptions. The techniques he applied, metadata-driven validation, real-time anomaly detection, and modular transformations with version control, are becoming standard in data engineering.

Future systems will go further. Detection tools will handle straightforward errors automatically and route complex cases to human reviewers. Governance structures will need to keep pace, making sure automated decisions can be audited and explained when regulators come knocking. In public systems, showing how models reach conclusions matters as much as getting the right answer.

The work in Mississippi's SNAP operations shows one way forward. Legacy infrastructure doesn't have to be thrown out to add modern tools. Intelligence can be layered in, tested under real conditions, and expanded gradually. Srinubabu Kilaru's work proves that agencies can upgrade their pipelines without risking the stability of systems that millions depend on. The challenge now is replication, taking what worked in one state and adapting it to the dozens of others still running on batch schedules and hoping for the best.