The European Space Agency (ESA) has unveiled stunning new photos that reveal the layers of Olympus Mons, the largest volcano on Mars. It is 26 km high, or roughly three times as tall as Mount Everest, with a base that stretches over 600 km.

Beyond its size, however, the most recent views show something much more fascinating: frozen "lava tongues" slithering down its slopes, an enigmatic horseshoe-shaped channel carved into the plains below, and what might be the precise path where water used to flow at the volcano's base.

After being too thrusty for years, probably millions, a poet would have compared it to a tongue that solidified into a rock.

However, according to ESA, it is actually just a rock formed of lava that has solidified and may have carried water into the Martian surface. The photographs, taken by ESA's Mars Express orbiter, provide the best view to date of the volcanic and potentially hydrological processes that sculpted this extraterrestrial landscape.

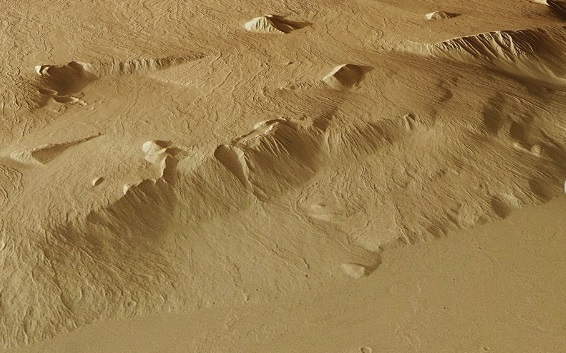

New photos reveal a huge scarp that completely encircles Olympus Mons and is a sheer cliff up to 9 km high. Ancient mega-landslides that pushed debris across the Martian plains for hundreds of kilometers created it.

Layered lava fields where molten rock once flowed downhill can be seen on the southeast flank. Before cooling into solid rock, these flows created tubes, carved channels, and dispersed into fan-shaped deposits. The rounded, smooth "tongue-like" ends of some lava flows indicate the places where the molten material slowed and solidified before coming to rest on the plains.

It is possible that lava and flowing water were once carried by a characteristic horseshoe-shaped depression in the lower plains, suggesting a more intricate hydrological history on Mars.

ESA said on social media that "a horseshoe-shaped channel may once have carried not only lava, but water." There are very few small craters in the area, indicating that the terrain is geologically young—possibly tens of millions of years old—and very recent in Mars' 4.6-billion-year history.

NASA's Mariner 9 spacecraft made the initial discovery of Olympus Mons in 1971. Scientists thought it was a mountain at first, but later missions showed what it really was.

Olympus Mons is thought to have formed during the early geological period of Mars, some 3.5 billion years ago. Since there have been no recent eruptions, the volcano is regarded as dormant. Its mild slopes and absence of impact craters point to a surface that was formed by lava flows and is therefore relatively young.

A large subterranean liquid water reservoir located deep within the Martian crust was previously found by scientists examining data from NASA's InSight mission. At a depth of roughly one mile (1.6 kilometers) below the surface, this water is trapped in microscopic cracks and pores in the rock.

The results offer fresh perspectives on the ancient climate and geological past of Mars by indicating that there may be enough water on the planet's surface to fill oceans. Interestingly, this reservoir represents liquid water rather than frozen ice, which raises the possibility that it could harbor subterranean microbial life, much like Earth's subterranean habitats.