Treatment of bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, had no clue or cure 70 years ago until psychiatrist John Cade discovered the miraculous drug that is now widely used to help patients regain stability.

Weaving a tale around discovery of Lithium as a drug in a biography of the pioneer psychiatrist who discovered it, Prof. Walter A. Brown from Brown University, has meticulously traced the research, theories, and people behind the finding in his new book.

The 1949 discovery of John Cade is revolutionary in the field of pharmacology since bipolar disorder, a relentless cycle of emotional highs and lows, is known to affect around 1 in 100 people globally today. If untreated, the disorder can increase the suicide rates among patients by 10 to 20 times.

Cade's paper "Lithium Salts in the Treatment of Psychotic Excitement" described, for the first time, that lithium carbonate — derived from the light, silvery metal lithium — can reduce the disorder by ten fold because of its astonishing efficacy in preventing the recurrence of manic-depressive episodes.

Lithium till then was avoided as a dangerous substance in the pharmaceutical industry, with little incentive to promote this naturally occurring drug, which could not be patented.

According to Brown's narrative, Cade began finding a link between the disorder and its symptoms during World War Two, when he was forced to be in charge of the psychiatric section at the notorious Japanese prisoner-of-war camp located at Changi in Singapore.

The psychiatrist began his investigation after the war at an abandoned pantry in Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital near Melbourne in Australia, where he started collecting urine samples from people with depression, mania and schizophrenia to discover whether some secretion in their urine could be correlated to their symptoms.

He then injected the urine samples into the abdominal cavities of guinea pigs, raising the dose until they died. In the process, he noticed that lithium carbonate reduced the toxicity of patients' urine that made the trick.

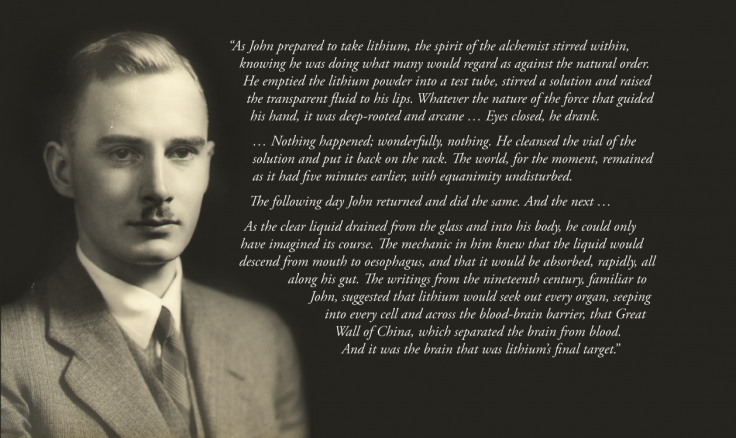

Raising the dose had a calming effect on the animals which made Cade wonder whether lithium could have the same tranquilizing effect on his patients. He then tried it out on himself to establish a safe dose.

He further treated ten people with mania and in September 1949 reported dramatic improvements in all of them in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Brown underscores the humble condition of his laboratory as the secret behind Cade's success as he was free to follow his curiosity, which is not possible now with many restrictions on conducting lab experiments or clinical trials.

Initially, his finding largely went unnoticed and Cade abandoned his experiments in 1950 after one of his patients, a man with a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, died from lithium poisoning.It was Mogens Schou, a Danish psychiatrist, who followed the clue from cade to test on his brother who had the bipolar disorder successfully.

Schou teamed up with fellow psychiatrist Poul Baastrup to carry out more tests and conduct clinical trials to establish that Lithium was an effective cure to bipolar disorder. His finding was published in The Lancet journal in 1970.

Today, Lithium is a widely accepted cure for the disorder though the dose needs to be carefully monitored as it has side effects such as nausea and trembling.

Capturing the journey to discover the cure by cade, Brown says in his book titled, "Lithium: A Doctor, a drug and a breakthrough," that it is highly unlikely for a modern researcher to get permission for such experiments which Cade was able to do on his own.