Antibiotic resistance bacteria which is currently one of the biggest global health threats, avoid antibiotics by changing their genome, a study has revealed.

The research said bacteria not only can pump the antibiotics out or break them down and even stop growing and dividing, which makes them difficult to spot for the immune system but can also "change shape" in the human body to avoid being targeted by antibiotics.

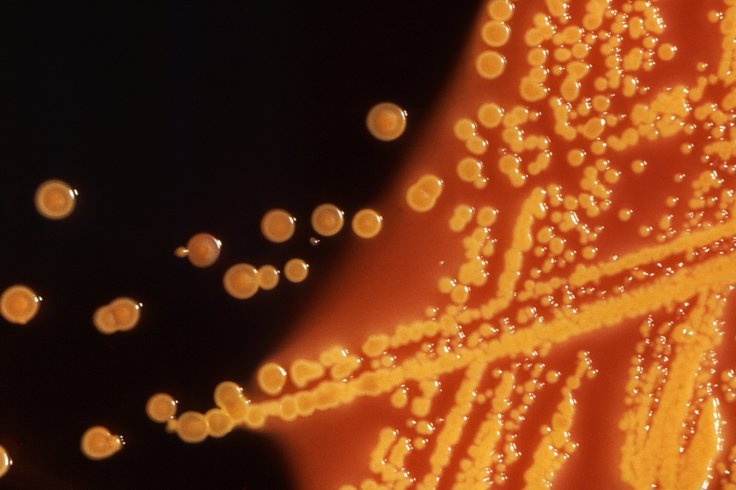

The research published in Nature Communications that specifically examined bacterial species associated with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), found that many different bacteria such as E. coli and Enterococcus can survive as L-forms which required no genetic modification for them to continue growing in a human body.

The development is a significant step in the direction of finding a cure for antibiotic-resistant bacteria, estimated for 700,000 deaths across the world each year, which currently are attributed to widespread antibiotic use.

Antibiotic resistance is predicted to cause 10 million deaths a year by 2050 as the global threat has also made numerous infections such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and gonorrhea harder to treat.

The researchers say it is easy for antibiotics to recognize and target bacteria as they are surrounded by a cell wall -- a thick jacket which protects against environmental stresses and prevents the cell from bursting -- gives them a regular shape (a rod or a sphere) and helps them divide efficiently.

Human cells do not possess a similar cell wall (jacket) and hence it is easy for the immune system to recognize bacteria as an enemy because of the noticeably different wall. Most commonly used antibiotics such as penicillin target the wall and kill bacteria without harming us, the researchers revealed.

Bacteria manage to turn into "L-forms" as they occasionally can survive without cell wall if the surrounding conditions are able to protect the bacteria from bursting.

Bacteria without a cell wall often lose their regular shape, become partially invisible to our immune system, and completely resistant to all types of antibiotics that specifically target the cell wall, the findings said.

"This is something that has never been directly proven before. We were able to detect these sneaky bacteria using fluorescent probes that recognize bacterial DNA," said a researcher, emphasizing the need for further research using more patients.

The authors hoped their findings would help find a way to clear these sneaky bacteria from the human body by combining cell wall active antibiotics with ones that would kill L-forms.