The renewed debate around jihad in India has been sharpened by a recent controversial statement by Maulana Mahmood Madni, a prominent Deobandi cleric, which once again brought the theological, political, and ethical meanings of jihad into public discourse. While the statement was defended by supporters as contextual and misunderstood, it also revealed how deeply fragmented contemporary Muslim interpretations of jihad have become. This moment of controversy underscores the urgency of revisiting influential ideological texts that shaped modern political understandings of jihad, most notably Maulana Abul A'la Maududi's Al-Jihad fil Islam, and examining how such reinterpretations continue to inform, confuse, and at times radicalise public debates today.

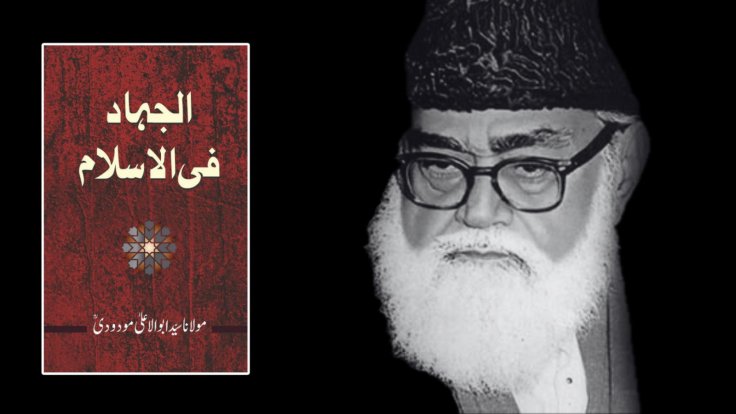

The concept of jihad has occupied a central yet carefully regulated place in classical Islamic thought. Rooted in jurisprudence (fiqh), ethics, and historical context, it was never conceived as a perpetual state of war, but rather as an exceptional instrument governed by stringent moral and legal constraints. However, in the twentieth century, this understanding underwent a radical reinterpretation. One of the most influential texts in this transformation was Al-Jihad fil Islam, written by Maulana Abul A'la Maududi (founder of Jamat E Islami) in the 1930s. While often defended as a product of colonial resistance, the book's ideological framework has had far-reaching and deeply troubling consequences. This article argues that Al-Jihad fil Islam represents not a continuation of classical Islamic jurisprudence but a decisive break from it, recasting jihad as an ideological and political project whose legacy has contributed significantly to contemporary extremism.

Classical Sunni scholarship treated jihad as a legal category bound by conditions: legitimate authority, defensive necessity, proportionality, protection of non-combatants, and the preservation of social order (dar' al-fitna). Maududi, by contrast, approached jihad through the lens of modern political ideology. Influenced by revolutionary movements of his era, he framed Islam as a comprehensive system seeking global supremacy, in direct competition with nationalism, democracy, socialism, and secularism.

In Al-Jihad fil Islam, jihad is no longer an exception regulated by law; it becomes a permanent, systemic struggle to dismantle "un-Islamic" orders. This redefinition marks a crucial shift from jurisprudence to ideology, from restraint to mobilisation.

One of the most problematic aspects of Maududi's argument is its rigid binary construction of the world. Humanity is divided between an Islamic system and a hostile Jahili order. Coexistence with non-Islamic systems is described as temporary and tactical rather than principled. Such a framework leaves little room for pluralism, constitutional citizenship, or peaceful political participation. This worldview resonates strongly with later extremist narratives, which portray democratic states, including Muslim-majority ones, as illegitimate and therefore lawful targets of violence. The language may differ, but the ideological grammar remains strikingly similar.

Maududi's conception of jihad is explicitly state-centric and militarised. He envisages an organised vanguard that captures state power and deploys it to reshape society and, ultimately, the world. War is not merely defensive; it is justified to remove political obstacles to Islamic sovereignty (Hakimiyyat-e-Ilahi). This approach collapses the distinction between moral reform and armed coercion. In doing so, it undermines one of the core principles of Islamic ethics: that faith cannot be imposed by force. The Qur'anic injunction "There is no compulsion in religion" is subordinated to political expediency.

It would be historically inaccurate to claim that Maududi directly advocated terrorism. Yet it would be equally naïve to ignore how his ideas travelled. His writings profoundly influenced later ideologues such as Sayyid Qutb and movements ranging from Jamaat-e-Islami to more violent offshoots across South Asia and the Middle East. The notion of jihad as a global ideological war became a cornerstone of modern jihadist thought. Terrorist organisations did not invent their worldview in a vacuum. They inherited a language that legitimised violence for political ends, stripped of juristic restraint and ethical nuance.

For many Indian Muslim scholars, particularly within Sufi-Sunni traditions, Maududi's thought appears alien to the subcontinent's Islamic experience. Islam in South Asia historically flourished through spiritual persuasion, cultural synthesis, and ethical example, not through revolutionary conquest. The radicalisation of jihad into a political weapon has not only distorted Islamic theology but has also harmed Muslim communities by fostering alienation, surveillance, and social mistrust.

Al-Jihad fil Islam must be read not merely as a historical text, but as a cautionary case study in how religious concepts can be reengineered into ideological weapons. By transforming jihad from a legally constrained act of defence into a permanent revolutionary struggle, Maududi helped lay the intellectual groundwork for later extremism. In an age where violent movements continue to invoke Islam for political ends, revisiting and critically interrogating such texts is not an academic luxury; it is a moral and social necessity. The future of Muslim societies, and their relationship with the wider world, depends on reclaiming an Islamic ethic rooted in restraint, pluralism, and human dignity rather than perpetual conflict.

[Disclaimer: This is an authored article by Dr. Shujaat Ali Quadri, who is the National Chairman of Muslim Students Organisation of India MSO. He writes on a wide range of issues, including Sufism, Public Policy, geopolitics, and information warfare.]