The first new type of plasma wave in Jupiter's aurora has been observed and analyzed by researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, leading to a new discovery.

Understanding "alien aurora" on other planets helps us better understand how Earth's magnetic field shields us from the sun's damaging radiation.

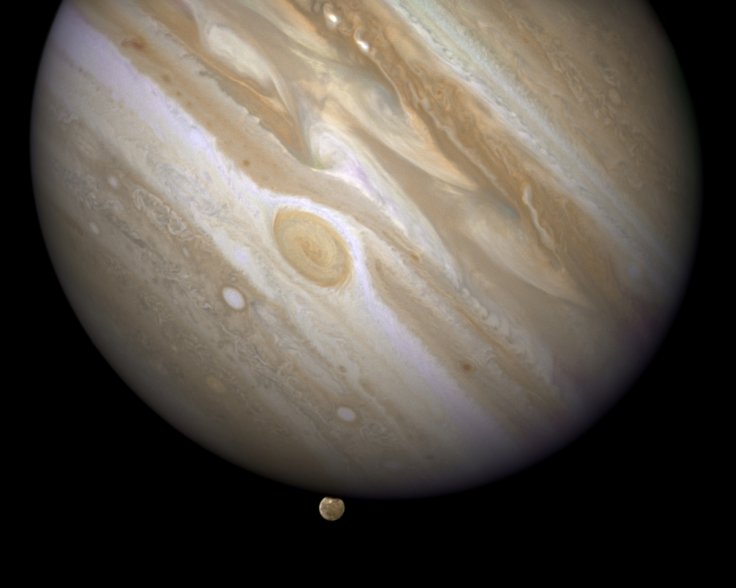

The team was able to apply their expertise in data analysis to examine data from Jupiter's northern polar regions for the first time thanks to data from NASA's Juno spacecraft, which made a historic low orbit flight over the planet's north pole.

Ali Sulaiman, an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy, said, "The James Webb Space Telescope has given us some infrared images of the aurora, but Juno is the first spacecraft in a polar orbit around Jupiter."

Plasma, a superheated state of matter where atoms split into electrons and ions, fills the space surrounding magnetized planets like Jupiter.

The gases light up as an aurora as a result of these particles being accelerated toward the planet's atmosphere. This manifests as recognizable blue and green lights on Earth. However, only UV and infrared instruments can see Jupiter's aurora, which is normally invisible to the human eye.

The team's analysis showed that the plasma waves have a very low frequency, unlike anything previously seen around Earth, because of Jupiter's strong magnetic field and extremely low density of polar plasma.

Robert Lysak, a professor in the University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy and an expert on plasma dynamics, said, "While plasma can behave like a fluid, it is also influenced by its own magnetic fields and external fields."

The study, published in Physical Review Letters, also clarifies how, in contrast to Earth, where the aurora forms a donut pattern of auroral activity around the polar cap, Jupiter's complex magnetic field permits particles to flood into the polar cap. As Juno continues its mission to support additional research into this emerging phenomenon, the researchers hope to collect more data.

Lysak and Sulaiman were joined by researchers from the University of Iowa, the Southwest Research Institute, and Sadie Elliott, a researcher with the School of Physics and Astronomy.