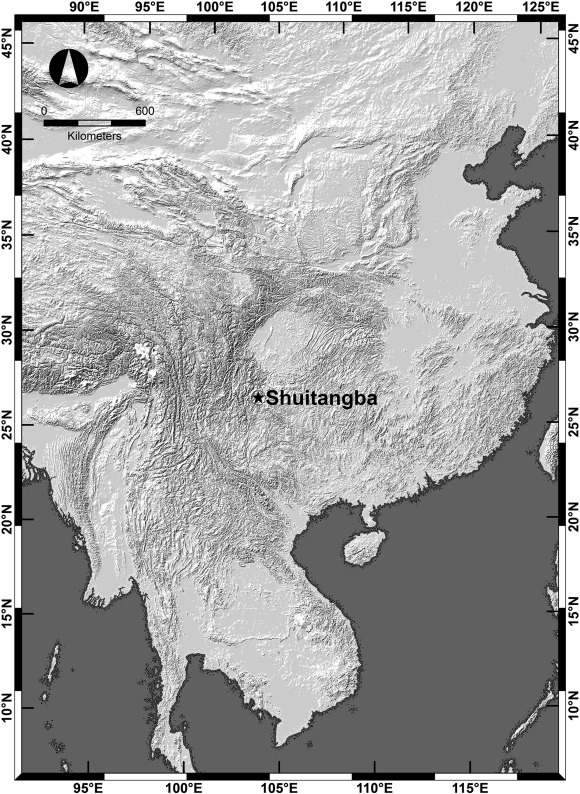

The beauty of fossilized remains is that the finding of one can often rewrite millions of years of evolutionary history. Now, three fossils around 6.4 million-years-old discovered at a lignite mine in southeastern Yunan Province, China by an international team of researchers suggest that monkeys existed in Asia alongside apes, and probably were the ancestors of several of the modern monkeys found on the continent.

According to Nina G. Jablonski, co-author of the study, the fossils are some of the oldest monkey fossils discovered outside Africa. It is close to or actually the ancestor of many of the living monkeys of East Asia. One of the interesting things from the perspective of paleontology is that this monkey occurs at the same place and same time as ancient apes in Asia," she said in a statement.

A 'Lady' Preserved in Time

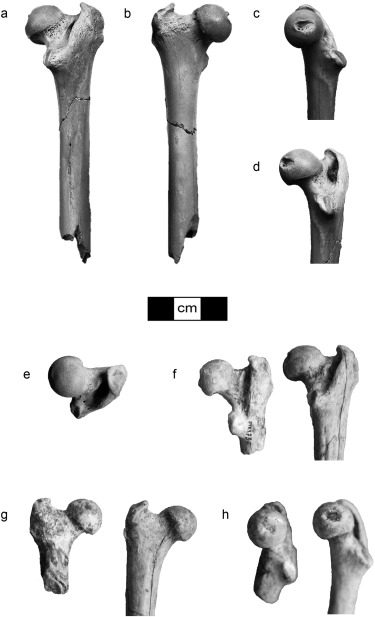

Unearthed at the Shuitangba lignite mine—this has yielded several fossils—was studied extensively by the international team of experts. They found a mandible and proximal femur, which they believe may belong to the same individual. Also, discovered was a left calcaneus or heel bone. These bones belong to the same species of monkeys found in Greece—Mesopithecus pentelicus.

Explaining what insights the bones offer, Jablonski said, "The significance of the calcaneus is that it reveals the monkey was well adapted for moving nimbly and powerfully both on the ground and in the trees. This locomotor versatility no doubt contributed to the success of the species in dispersing across woodland corridors from Europe to Asia."

"Jack of All Trades"

According to the scientists, the upper portion of the leg bone and lower jawbone suggest that the specimen was a female. The authors strongly opined that these monkeys may have been "jacks of all trades" with the ability to move effortlessly both on land and on trees. Also, the structure of the teeth offers evidence that they consumed a wide range of fruits, flowers and plants, unlike apes that mostly ate fruits.

"The thing that is fascinating about this monkey, that we know from molecular anthropology, is that, like other colobines (Old World monkeys), it had the ability to ferment cellulose. It had a gut similar to that of a cow," added Jablonski.

Guts Like Cows

These monkeys could thrive because of their ability to consume low-quality food high in cellulose and acquire enough energy through the fermentation of food. Subsequently, they utilized the fatty acids that were then available from the bacteria. Interestingly, this pathway is very similar to ones that several modern-day ruminant animals such as cows, goats and deer are known to possess.

Describing the biological processes that separated these monkeys from apes, Jablonski illustrated, "Monkeys and apes would have been eating fundamentally different things. Apes eat fruits, flowers, things easy to digest, while monkeys eat leaves, seeds and even more mature leaves if they have to. Because of this different digestion, they don't need to drink free water, getting all their water from vegetation."

Adapting to Become Survivors

With such adaptations, these monkeys did not have the compulsion of living around water bodies and could weather drastic climatic changes. Jablonski said that these monkeys were the same as the one that was found in Greece around the same period, suggesting that they disperse from some in central Europe and spread rather quickly. "That is impressive when you think of how long it takes for an animal to disperse tens of thousands of kilometers through forest and woodlands," expressed Jablonski.

Though sufficient evidence is available to declare that these species originated in Eastern Europe and expanded from there, the scientists are yet to understand the evolutionary pattern of this rapid dispersal. At the end of the Miocene—a geological period characterized by dramatic environmental changes 23.03 to 5.333 million years ago—these monkeys began moving out of Eastern Europe. This was around the time across the world other than Africa and pockets of Southeast Asia were becoming extinct.

Calling the site of fossil a snapshot of the period where the last of apes existed alongside new order monkeys, Jablonski said it testifies to the value of versatility and adaptability in diverse and changing environments. "It shows that once a highly adaptable form sets out, it is successful and can become the ancestral stock of many other species."