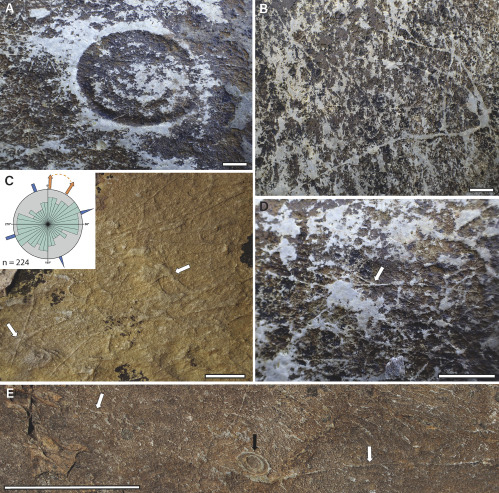

Billions of years ago, life forms first appeared on earth. Recently a new study revealed that some of the first creatures on the blue planet were connected by networks of thread-like filaments. These fossil threads were recently discovered by the scientists from the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford.

The scientists revealed that these fossil threads, including some threads which are four meters long, found to be connected organisms known as rangeomorphs, which had dominated earth's ocean world almost half a billion years ago.

The ancient social networking

The team of UK scientists found these filament networks, which were apparently used for the nutrition-communication-reproduction in seven species, found at almost 40 different fossil sites in Newfoundland, Canada.

The research report, published in the journal Current Biology, revealed that towards the end of the Ediacaran period when world's first diverse communities of large and complex organisms began to appear. The Ediacaran period spanned over 94 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period 635 million years ago to the statement of the Cambrian Period. Prior to this era, almost every living creature on planet earth used to be microscopic in size.

Scientists claimed that these fern-like rangeomorphs, a form taxon of frondose Ediacaran fossils that are united by similarity to Rangea, were some of the most successful life forms during that time, which could grow up to two meters in height and populate large areas of the seafloor.

Early life on earth

As per the researchers, it could be believed that these reangeomorphs may have been some of the first animals to exist on the blue planet. But their unusual anatomies have puzzled palaeontologists for years as these creatures did not have mouths, organs or means of moving. Some experts also suggested that early earth creatures absorbed nutrients from the water around them.

It should be noted that while these early animals could not move and are preserved where they lived, scientists believed that there is a possibility of analyzing the whole population of reangeomorphs from the fossil record. Early studies revealed that the creatures have looked at how these organisms managed to reproduce at that time.

The lead author of this newly published study, Dr Alex Liu from Cambridge's Department of Earth Sciences, said that reangeomorphs seem to have been able to quickly colonise the ocean floor and "we often see one dominant species on these fossil beds. How this happens ecologically has been a longstanding question—these filaments may explain how they were able to do that."

The study on earth's earliest creature

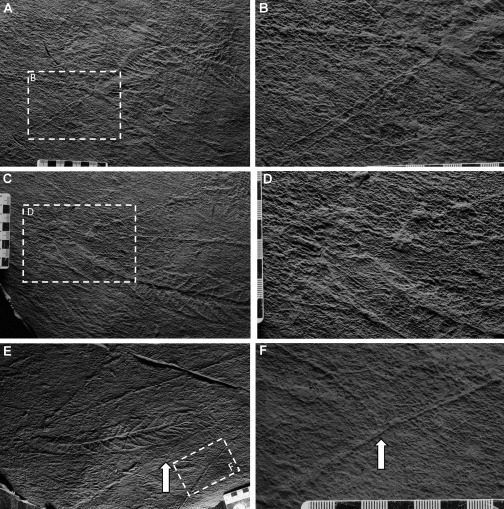

As per the finding, most of the threads were discovered between two and 40 centimetres in length. But it should be noted that since the filaments are very thin, these are only visible in places where fossil preservation is exceptionally good. For this study, the scientists found the fossils on one of the world's richest sources of Ediacaran fossils, on the five sites in eastern Newfoundland.

Scientists said that it is possible that the filaments may have provided stability against strong ocean currents and enabled organisms to share nutrients. Lui said, "We've always looked at these organisms as individuals, but we've now found that several individual members of the same species can be linked by these filaments, like a real-life social network," and added that the team of researchers may need to reassess earlier studies to understand how these ancient organisms interacted and how they competed for space and resources on the ocean floor.

In addition, the co-author of the study, Dr Frankie Dunn from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, stated that the incredible fact is the level of details preserved on these sea floors while some of these filaments are only a tenth of a millimetre wide.