Alligators and crocodiles are the closest we have to modern-day dinosaurs. These unique reptilians are known for their awesome power and their deadly predatory instincts, and their armor-like hides that are hard to penetrate. Though, unlike other lizards, they are not known to regenerate their tails. Now, a study has found that American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) can indeed re-grow their lost tails.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and Arizona State University has discovered that young alligators possess the ability to regenerate their tails to lengths of up to three-quarters of a foot, or around 18 percent of their complete body length.

"What makes the alligator interesting, apart from its size, is that the regrown tail exhibits signs of both regeneration and wound healing within the same structure," said Dr. Cindy Xu, lead author of the study, in a statement.

The Rare Gift of Regeneration

Humans, along with other mammals, birds, lizards, and alligators, are members of a group of vertebrates known as amniotes. Dinosaurs also belonged to this group. Amniotes are animals that retain the fertilized egg inside the mother or lay their eggs externally. Of the mentioned species, only lizards have been known to be equipped with the evolutionary advantage of regenerating their lost body parts, specifically their tails.

Lizards such as common house gecko, chameleons, and monitors, among others, are those whose regenerative capabilities are observed commonly in nature and in our own back yards. However, the finding that alligators are capable of re-growing complex new tails sheds new light on the regeneration process in amniotes.

A Secret Hidden In Alligator Tails

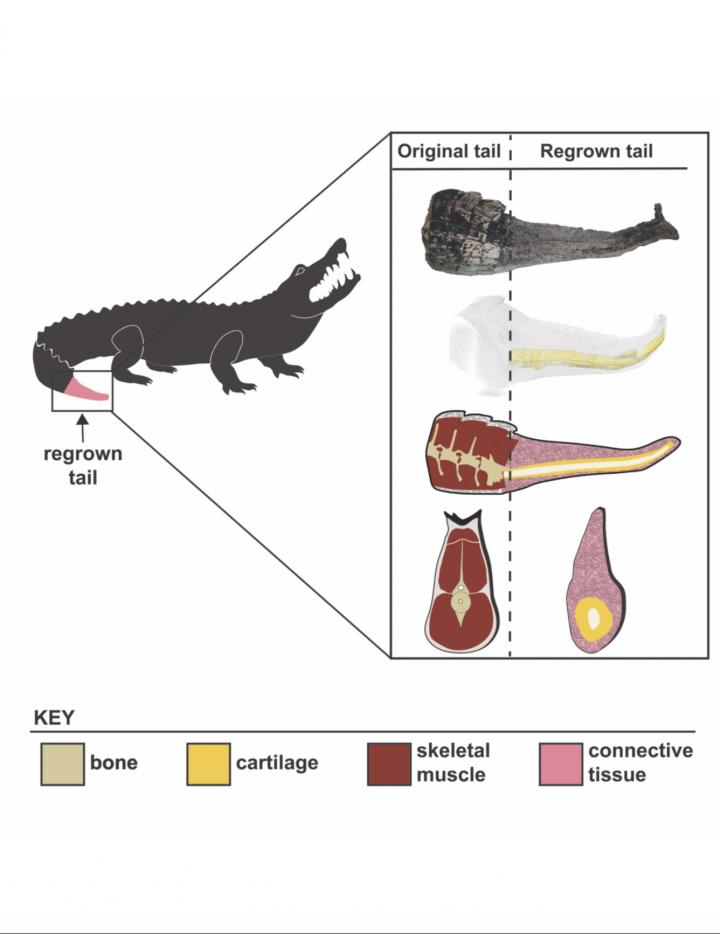

For the study, the authors used demonstrated methods of analyzing anatomy and tissue organization, along with advanced imaging techniques to examine the re-grown tails of juveniles or sub-adult alligators. The authors discovered that the new tails were immensely complex structures. They had a central skeleton that was composed of cartilage which was encompassed by connective tissues. Blood vessels and nerves were interlaced with these connective tissues.

Dr. Xu explained that the re-growth of cartilage, nerves, blood vessels, and scales, were found to be in accordance with older studies on the regeneration of lizard tails. "However, we were surprised to discover scar-like connective tissue in place of skeletal muscle in the regrown alligator tail. Future comparative studies will be important to understand why regenerative capacity is variable among different reptile and animal groups," she added.

An Ability Like No Other

Prof. Kenro Kusumi, co-senior author of the study, pointed out that the ancestors of alligators, birds, and dinosaurs, diverged approximately 250 million years ago. He noted that an interesting evolutionary difference emerged between birds and alligators—while alligators held on to their intricate cellular mechanism of regenerating complex tails, birds lost it.

This leads to the question of when during the course of evolution this ability disappeared in birds. "Are there fossils out there of dinosaurs, whose lineage led to modern birds, with regrown tails? We haven't found any evidence of that so far in the published literature," speculated Prof. Kusumi.

According to Prof. Rebecca Fisher, co-author of the study, averred that these findings can have a larger and wider impact. "If we understand how different animals are able to repair and regenerate tissues, this knowledge can then be leveraged to develop medical therapies," she stated.