One of the most interesting questions about the human anatomy for the medical field is how to prevent hair loss. Providing insights into the resolution of the mystery, a new study claims that a hair-growing mass of human skin has been created in the lab.

According to the study published in Nature, scientists were able to create hair-bearing human skin organoid, making it the first of its kind. This could help develop models to prevent hair fall or even reverse it in the future.

"We anticipate that our skin organoids will provide a foundation for future studies of human skin development, disease modelling and reconstructive surgery," the authors wrote.

Organoids From Early Embryonic Cells

Organoids are small and self-organized three-dimensional tissue cultures that are grown in labs. They are derived from stem cells. These cell cultures can be modeled to replicate most of the complexity of an organ, and in some cases, manifest particular aspects of it such as the production of certain kinds of cells.

For the study, the pluripotent stem cells were used to grow the hirsute or hair-growing skin. Pluripotent stem cells are master cells that are found during the early embryonic stages of development. They diversify into specific cell types during the later stages of the embryo's development.

The study was led by Dr. Karl Koehler from Boston Youngsters' Hospital. Benjamin Woodruff, an Oregon Well Being & Science College graduate, assisted in the creation of organoids as a post-baccalaureate analysis technician within the Stanford College lab.

Cells Mimicking Human Skin

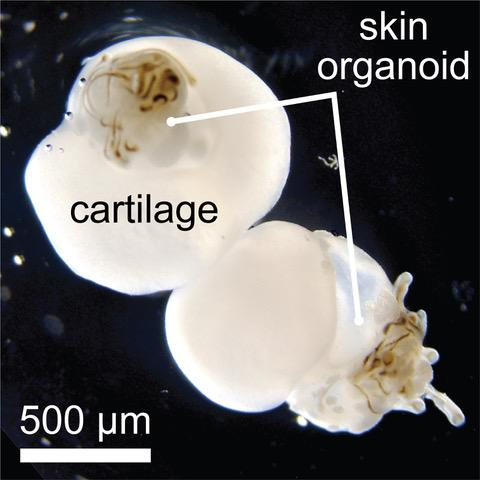

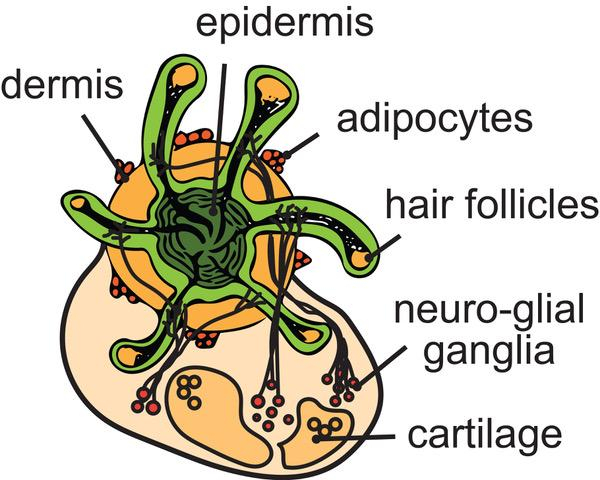

The scientists reported that during an incubatory period of 4-5 months, a skin organoid resembling a cyst emerged. It was composed of a layer of the stratified or assembled epidermis (outermost layer of skin), a fat-laden layer of the dermis (living tissue beneath the epidermis), and pigmented hair follicles that were accompanied by sebaceous (secretory) glands.

The organoid also had a sensory network of neurons and cells known as 'Schwann' cells that form nerve-like clumps. These target cells are known as 'Merkel cells' in the hair follicles present in the organoid, thereby, replicating neural circuitry linked to human touch.

Growing Hair-bearing Skin

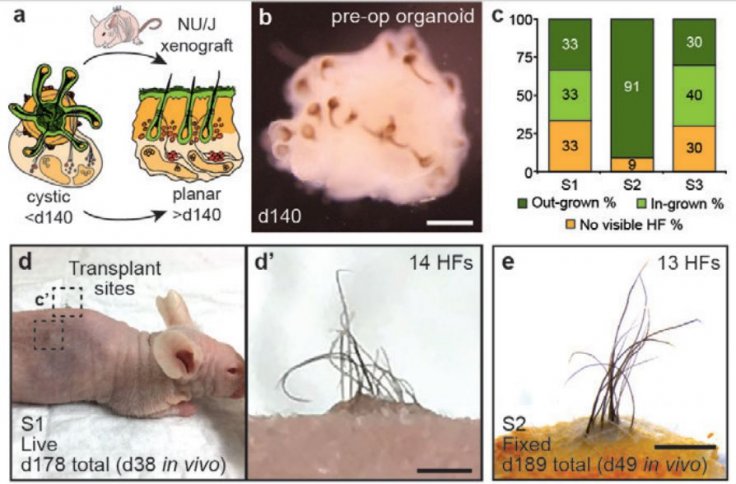

In order to understand more about the human skin organoids, it was subjected to tests. The first was a single-cell RNA sequencing. It was followed by direct comparison to fetal specimens. The analysis revealed that the skin organoids were very similar to the facial skin found in human fetuses during the second trimester of the gestation cycle.

Furthermore, in vivo experiments of grafting the organoids on to 5-6 week-old female immunodeficient nude mice were performed. It was that the organoids were able to form planar hair-growing skin on the mice.

Provides New Avenues for Hair-related Research

Through the study, the authors were able to demonstrate that nearly complete skin can assemble itself in vitro and can be used to cultivate skin in vivo. This method also eliminates the need to acquire skin samples from human beings to conduct research on human hair.

Explaining its benefits, Woodruff said, "This makes it possible to produce human hair for science without having to take it from a human. For the first time, we could have, more or less, an unlimited source of human hair follicles for research." Such access to an abundant supply of hair-bearing skin can enable researchers to learn more about the development and growth of hair and may unlock clues in process of reversing hair loss.